The Other Oppenheimer

The film Oppenheimer brings back memories of Robert Oppenheimer’s brother Frank, a colleague from my days as a museum director. I knew him years after he worked on the nuclear bomb with Robert. Frank started the Exploratorium three years before I incorporated Impression 5 Science Center in Lansing, Michigan in 1972. I met him that summer while my husband worked at Stanford and I toured museums. During our stay, a friend and I went to see the Exploratorium in San Fransico with five children in tow.

I was overwhelmed by the size of the Palace of Fine Arts, the building the science center occupied, but was underwhelmed by the number of exhibits. The building was poorly lit, with interactive displays covering one-third of the floor, with the rest filled with airplanes. As I walked through the hall, I waved my hand through a rock hovering in space above a barrel. The illusion of a floating object became one of the early exhibits I added to my Lansing Museum.

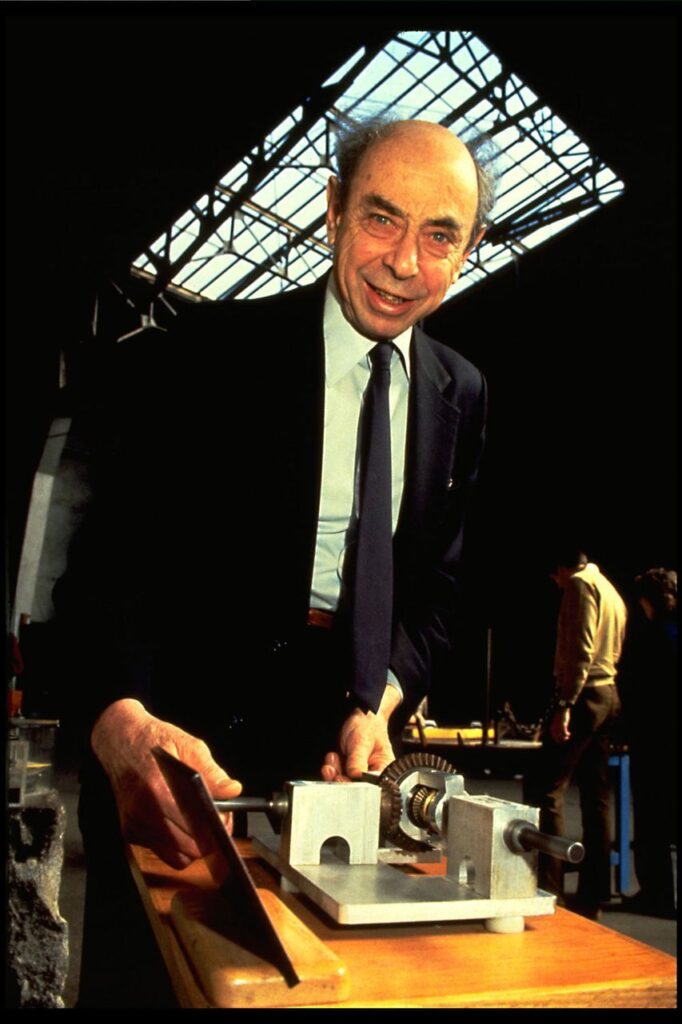

Frank greeted me in a trailer office in the center of the building. It was the only place that was heated and air-conditioned. He was perched like a bullfrog on the seat of his chair, squatting the whole time we talked. Our conversation was animated as we discussed interactive teaching methods and lamented the difficulty of raising money for our ventures.

After spending a pleasant morning, I was horrified to find I had locked my keys inside my car. Frank saved the day by inserting a wire under the rubber at the top of the window and pulling up the lock, a feat impossible today. Over the next eighteen years, until his death, our paths crossed often at conferences, meetings, and workshops.

Frank Oppenheimer was a nuclear physicist who became a science center director by chance after being blacklisted for belonging to the communist party. Banned from university positions, he sold an inherited Van Gogh painting to purchase a ranch in Colorado. He was an angry, confused, unhappy man until McCarthyism ended and a local school lost its physics teacher. The administration begged him to take the position, and a new life took off.

Frank turned their poorly attended science class into a top contender at the Colorado State Fair. His teaching methods ensured that pedantic material came alive, making the bored children of ranchers into student scientists. From teaching high school, he went to the University of Colorado, where he returned to particle physics research and taught, but his interest in science education never wavered. It led to his developing a “Library of Experiments” for educators. With new these new methods in hand, he made his dream of starting a science center a reality by founding the Exploratorium in 1969.

Three years later, when I became involved, there were fewer than twenty science centers sprinkled across the U.S. Only sixty-five of us attended the first Association of Science and Technology Center (ASTC) gathering. With National Science Foundation funding, the fledgling group started when the American Association of Museums (now the Alliance) wouldn’t recognize our centers as worthy of membership. The snub disappeared a few years later as the number of science centers, natural history museums, children’s museums, and nature centers with interactive displays grew into the thousands.

Our group of newbies looked up to Frank, who played an important leadership role in the development of hands-on learning in museums. We were a heady group of quasi-fanatics who attended workshops organized by the Exploratorium. There we complained about public school teaching, about how children were required to memorize science from textbooks. And, we weren’t happy with the push-button, copy-heavy commercialism of the twelve major science museums, including those in Philadelphia, Chicago, and L.A.

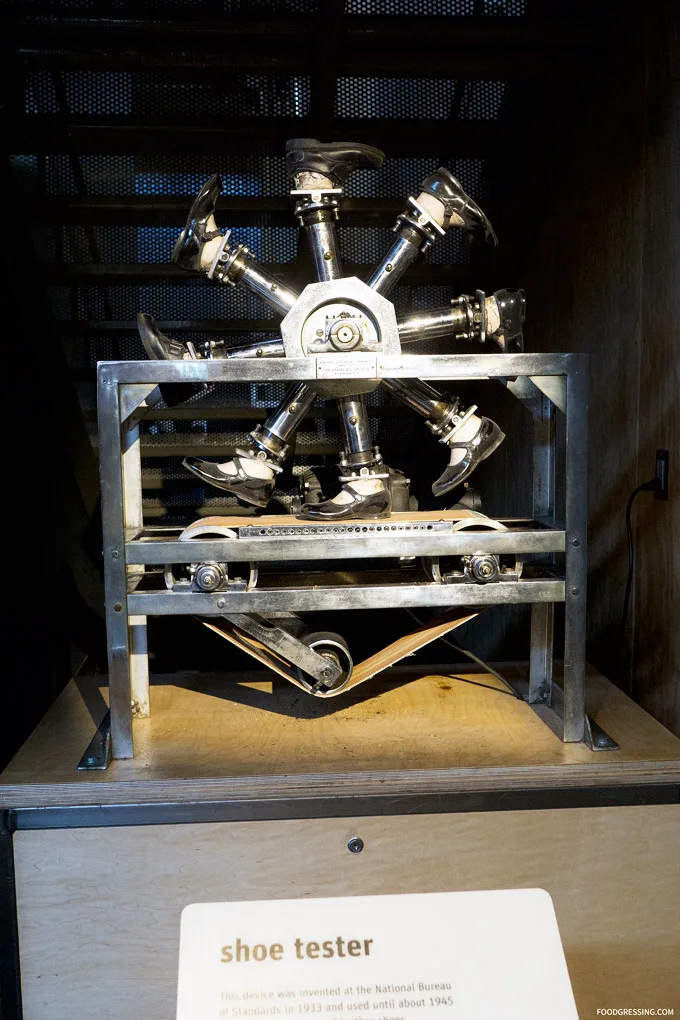

Frank was a Renaissance man promoting art and science and touting aesthetics, engineering, and technology as necessary elements for creative outcomes. Exploratorium displays weren’t in fancy cabinets. Yet they were sophisticated and built solidly. Their construction shop was open to the public to peer inside. If you ever played with a pin screen and made the pins pop up in the shape of your hand, you participated in a display by an artist funded by the Exploratorium. A few years later, a toy company illegally flooded the market with copies of the artist’s creation.

We shared ideas with Exploratorium staff and discussed ways of making thought-provoking problem-solving exhibits that wouldn’t fall apart when thousands of hands played with them. Frank never pushed ideas on us but rather opened opportunities for discussion. With my psychology background, I shared that children approached exhibits fearlessly, without reading instructions, while their timid parents read every word we put out. Our goal was to make the instructions more intuitive than lengthy while providing in-depth information to adults who didn’t mind reading.

Frank’s struggles were many, and his perseverance was admirable. His journey is one of twelve biographies included in Lives of Museum Junkies, a book I wrote about the trendsetters of the science museum movement. Frank was among us not knowing how to run a public institution. We learned the hard way how to attract volunteers, assure public safety, make dispids on the cheap, and manage our boards. e.

Building a museum from the ground up is expensive. We were poor and had to become handshaking fundraisers. Impression 5’s museum suffered by not having air-conditioning during boiling hot summers. Visitors to the Exploratorium needed hand warmers and overcoats during winter excursions.

Before the pandemic, the science centers and museums that were part of ASTC reported an annual attendance of over 62 million visits, with another 10.1 million people served in off-site events and programs such as school outreach. Those numbers plummeted during COVID and still haven’t grown to pre-pandemic levels.

Lives of Museum Junkies candidly addresses the mistakes we made and gives a behind the scene look at the challenges of running a public institution. Passionate and naive, we plodded along, working long hours to ensure our institution’s success. I say “naively” because many of us might not have started our projects if we knew what lay ahead.

I updated Lives of Museum Junkies to cover the trials brought about by COVID-19. It was a terrible time of closures when centers had to be inventive to survive. Every museum director included in the book tells a unique story. Though I’m definitely biased, I think you’ll find the stories inspiring. If you purchase from Amazon, please write a review. Though the first edition had dozens of positive reviews, they didn’t transfer to the second edition’s sale page. I need at least twenty-five more to ensure that these stories will inspire future generations to follow their passions.

Questions about museums. Contact me at marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

Please share your science center experiences below.