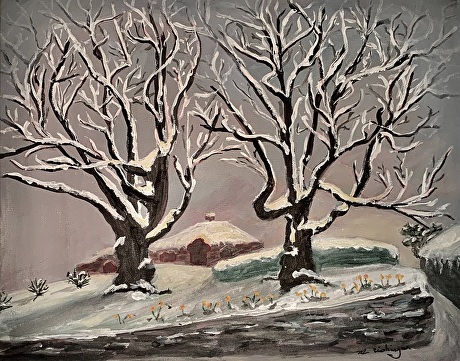

In Portland, Snow arrived late in 2019 and didn’t last long. During the first week we were sequestered I painted Spring Snow after noticing daffodils breaking though the snow at a neighbor’s house, imagining the pandemic would soon be over. Now, nine months later, I realize we have a long way to go. Yet, the pandemic will end and our world will continue turning in never ending cycles.

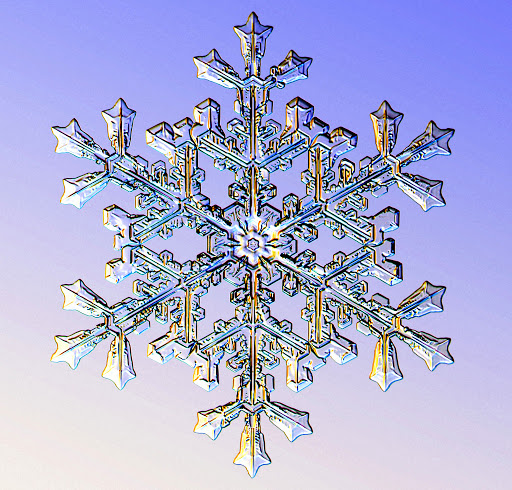

Snowflakes, like people, are unique.

The other day, I spied our snow shovel buried in the basement closet indicating it was time to move to the garage where it will be more accessible. The white caps of the Cascade Mountains expanded over the past month. It won’t be long before snow will creep from its high perches and descend on rooftops and sidewalks in the lower Willamette Valley.

I love the snow and wish Portland had more of it. Thirty-five years ago, I could cross country skiing through Washington Park during lunch breaks from work. That pleasure is long gone. Global warming has effected such escapades close to town.

The street I lived on as a child was entered on a high plain that swooped down to where my house was situated. When it snowed the children in my neighborhood spent the day whizzing down the hill on our sleds to see who could go the furthest. In those days, sleds were made of wood and had metal runners you steered with a cross bar. Plastic disks and molded toboggans didn’t exist.

We dressed in puffy snowsuits and boots that were more clumsy to wear than the cold-weather clothes sold in stores today. My Mom had hot chocolate waiting by the time we came in with frozen fingers and toes.

In addition to making snowmen, building forts and having snowball fights, my cousin Elaine and I would go to Grey Nuns Pond, not far from our house, to see if the ice was fit for skating. One year, against my Elaine’s advice, I took a few steps on the ice to a spot I thought was thick, when it cracked and I fell in. Thankfully, I was near the edge and didn’t drown. Elaine thought what happened hilarious and started laughing as I pulled myself out. I laughed so hard that tears came down my cheeks and I wet my pants, which amused her even more.

When my youngest son was seven months old son, my husband and I took him outside so he could see snowflakes falling from the sky for the first time. The delight and amazement on his little face as he stretched out his hand to capture them is imbedded in my memory forever.

Watching white fluffy precipitation blanket our one-hundred-year-old farmhouse was thrilling. I kept cross country skis on the porch and took off through neighboring farm fields with the moon lighting my way.

Snowflakes have always fascinated me. Though similar to their companions, each one is a unique ice crystal that develop as a result of thousands of distinct water molecules combining in random formations. The flakes are clear, not white, appearing that way because of how light is reflected through them. Like snowflakes, people too share a fleeting moment of individuality before disappearing into the mass of humanity.

Snow is a reminder that cycles control the seasons and all living matter. Water vapor rises to form into clouds before falling as flakes on mountain tops where they will melt and run through rivers into seas before rising again. We are like the flakes, individuals, united in societies that are born, grow and die in continuous cycles of transformation.

You might wonder how one is formed.

–Flakes, or snow crystals develop around a dust particle that grows into a hexagonal prism. It happens when water freezes and molecules join together to form six smooth sides. It takes approximately 100,000 water droplets to make one snowflake.

–The flake grows larger, becoming unstable, which causes the corners to sprout

arms.

–As it falls from the clouds, the crystal moves though different temperatures

and arms starts to grow on the arms.

–It keeps moving through more temperature changes that cause new growth to grow on the arms.

No Two Are Alike

Fun facts your teacher never told you.

- The world’s largest snowflake was just under 15 inches wide and 8 inches thick. It fell at Fort Keogh, Montana on January 28, 1887.

- Snowflakes fall at 3-4 miles an hour

- Each snowflake is made up of about 100,000 water molecules forming 200 ice crystals.

- 80% of the world’s water comes from snow.

- The most snowfall over a year was on Mount Rainier in Washington. It snowed 1, 224 inches between February 1971 and February 1972.

- Snow at the North and South Poles reflect heat into space. The snow acts like a mirror from the sun with light bounces off it and traveling into space.

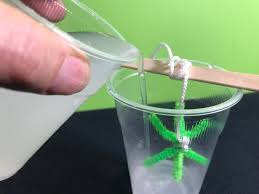

While sequestered it is good to stay busy.

Project 1: Have fun making watching crystals form as you make snowflake ornaments out of pipe cleaners to hang on you Christmas tree.

Supplies

Box of Borax detergent

Hot water

Wide mouth jars or paper cup

Pipe cleaners

Food dye if you want to color them

Process

- Shape various Christmas ornaments using pipe cleaners. For example, shape pipe cleaners into a stocking, star, or cross. Note: The shapes must fit into the jars.

2. Tie a string to the top of the ornament.

3. Fill jars with hot water.

4. Add three tablespoons of Borax to each jar of water with a few drops of food dye if you want to color them.

5. Lower the string so that the ornament is completely covered. And then tie the string around the top of the open jar to keep it in place.

6. Leave the ornaments in the water overnight.

7. Next day the Borax will have crystallized in the water and attached themselves to the pipe cleaner ornaments.

Why does it work?

Because Borax is an example of a crystal. Salt and sugar are other examples. Hot water molecules move away from each other. When you add Borax, the molecules make room for borax crystals to dissolve. But a point of saturation can be reached, meaning there will be some remaining crystals. As this water cools, the water molecules move closer together again. Crystals begin to form and build around another item in the water, such as the pipe cleaner. This is especially true as the water evaporates.

Project #2: Capture your own snowflakes

Supplies

A cold, winter day

black piece of foam board or paper

magnifying glass

Place the black paper or foam board outside, but out of the snow, for 15 – 20 minutes, or until snowflakes can land on it and not melt immediately. When the paper is cold enough place the paper on a level surface or hold it carefully where snowflakes can fall on it. Observe the collected snowflakes with the magnifying glass quickly before they disappear.