Labor in the Woods

A few days ago, I went to the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington to explore old growth Cedar trees for a picture I was painting. It seemed like a perfect way to celebrate the last days of summer and acknowledge the coming of Labor Day, a holiday that reminds us that the weather will start to cool and rains will come to drench the Northwest. As soon as I started up the trail, my mind was transported back to a time when the entire coastal region looked like the forest I was in. My imagination went wild with the thought that people once lived and labored in the woods I traversed.

It had been many years since I walked past trees as old as 1,500 years and I was overcome by earthy, woodsy smells that somehow felt warm and reassuring. I gazed at sphagnum moss hanging from limbs and the variety of green mosses blanketing lower trunks and roots. I felt good knowing that mosses harbor cynobacteria that convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that can be used by other plants.

Gifford Pinchot is one of the oldest national forests in the United States. Its 1.32 million acres include 198,000 acres of old growth pockets along the western slopes of the Cascade range between Mount Rainier and the Columbia River. Dense wooded areas benefit from a abundance of rainfall and a network of streams fed from glaciers on Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Adams.

Coastal natives were fortunate to live a place that served their needs so well. Tribal members labored together and didn’t have to travel far to acquire the food and materials for shelter needed. Washington tribes were wealthy in comparison to other Native American communities. With natural bounty around them, they became successful traders who traveled up and down the coast bartering their wares. During the winter months they had time to relax and develop their artistic culture Artisans were employed to carve totem poles and make masks for story tellers to use by the fire in front of mesmerized children. Women worked on beaded moccasins, wove baskets and made festival garments.

Eagle Mask

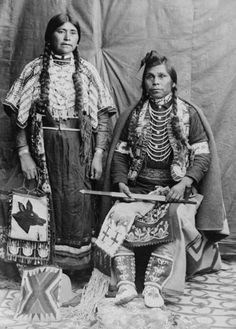

Yakama wife and husband (1908)

Together they built communal houses made from thick cedar planks as long as 100 feet. It must have been difficult to fell massive trees and split them into planks using beaver teeth and stone axes. Healers harvested medicinal plants. Women and children collected berries and tubers while men hunted elk and deer and fished in well stocked streams. The woods were full of species we now consider endangered. Natives heard the calls of spotted owls. They trapped beaver and easily caught coho and steelhead salmon for smoking in preparation for winter.

Foragers split the inner bark of Cedar trees into fine lacings and ties and wove them to make storage bags, baskets, finely twined mats and rain capes. Some were woven into hats decorated with a red dye made from the tree’s shavings. Twigs were boiled and sprinkled on hot stones or brewed into tea to relieve symptoms of Rheumatism. Large trees were hollowed to make canoes that could hold up to fifty people. They were strong enough to travel the length of the Columbia River and withstand battering waves of the ocean. The labor they performed was always in harmony with the land.

In 1855, the Klikitat, Palus, Wallawalla, Wanapam, Wenatchi, Wishram, and Yakama peoples signed a treaty that gave up ancestral lands that amounted to one quarter of the state of Washington. The Confederated Tribes agreed to live with the Bands of the Yakama Nation on a reservation with off-reservation resource rights. In 1916, the treaty was broken when the Washington State Supreme Court ruled that hunting and fishing off-reservation had to be done in accordance to state fish and game laws. It was no longer possible for Native people to live as they did generations earlier.

The reservation in eastern Washington is barely able to sustain itself. Its economy does not function well with timber sales down and unemployment at 73 percent. Tribal members live in extreme poverty. Health care and housing are inadequate, schools are failing with a high drop out rate, and the family unit is often non-existent. The women are twice as likely to be abused as the average Washington female and teens are more likely to commit suicide or die a violent death. COVID-19 has hit the Yakama Nation exceptionally hard, forcing them to postpone community gatherings.

As we approach Labor Day, I feel sad that we turned a proud people with a rich heritage into a shell of what they once were. Labor Day was started in 1882 to protest deplorable working conditions. The communal way of life that the Yakama Tribes thrived under is no more. Their working conditions are shattered and they are no longer able to sustain themselves. It is difficult to celebrate labor when it has to endure such a dire situation. As we recognize the importance of the men and women labor for their living, and hear the concerns of American workers, let’s not forget the people on reservations who need their world to be made right.

References:

Maxfield, D. (2016) 9 Revealing Stats that Show the Breakdown of Yakama society. Sacred Road Store. retrieved from https://sacredroadstore.com/9-revealing-stats-that-show-the-breakdown-of-yakama-indian-society/The

Yakama Tribal Council. (2018 )Proposal for an AmeriCorps program. retrieved from https://www.nationalservice.gov/sites/default/files/grants/17TN195273_424.pdf

Sager, J. (2020) 10 Fascinating Things You Probably Didn’t Know About the History of Labor Day and the Labor Movement. retrieved from https://parade.com/1081089/jessicasager/labor-day-history/

Art is always for sale: Western Red Cedar is mixed media on acrylic with a canvas base/ 16″ by 20″ / $ 375. For information contact me at marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

I enjoy hearing from you. Do comment below.