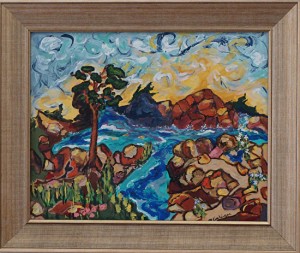

Rock Creek Awakens – Children need to be able to roam through rich environments like this acrylic landscape by Marilynne

Rock Creek Awakens – Children need to be able to roam through rich environments like this acrylic landscape by Marilynne

Freedom to Fail!

One October day, while sitting in my museum office, I heard shouting and the sound of feet running towards my door. Needless to say, I was alarmed, and vaulted from my chair imagining that there had been an accident. Instead, I was greeted at the door by a mother and teacher who were extremely excited and wanted to share incredibly good news. A miraculous event had occurred during their visit; Jenny, a six year old autistic child, spoke for the first time.

The women had been exploring my small Lansing science center with their class of disabled students, but because they had several youngsters to oversee, their attention was turned elsewhere and the young girl had freedom to explore the exhibit hall on her own. She had stopped before an oscilloscope, picked up the microphone, and in order to see the wiggly voice patterns, started making sounds. Jenny became mesmerized with the moving lines and repeated several words over and over again. Without pressure to perform, the child had felt comfortable playing with the display in her own way. Eventually, the adults went to find her, and from a distance observed what was happening. They were so amazed and excited that they immediately ran to give me their wonderful news.

The teacher later shared that she had forgotten about the research that had been conducted with autistic children suggesting use of an oscilloscope to help patients vocalize. The day’s dramatic event reminded her of the study and she said that she planned to requisition a scope for her classroom in order to integrate it into a therapy approach with several other students.

The story does not end here, however. Mother, teacher and child returned to the museum several weeks later, and immediately dovetailed to the oscilloscope. The child was placed in front, handed the microphone, and told to talk into it, while the adults stood behind observing with high expectations of a repeat performance. Instead, they saw what some of you might expect . . . silence. And though they were disappointed in the child’s reaction, it fascinated me for it provided insight into human behavior that reinforced some of my assumptions about learning.

What did this incident teach me? First, it confirmed my belief that children need a rich variety of environments through which to roam. Secondly, it corroborated my opinion that youngsters need freedom to make choices away from the eyes of overly anxious adults.

What I like most about science centers and children’s museums is that they provide a safe environment for self-exploration. They are designed to enable visitors to learn in their own way on their own time scale. Parents do not need to hover over children and teachers are not charged with explaining what should be learned. A child exploring the interactive displays, experiments and forms his or her own conclusions. Very quickly the young visiter learns that it OK to be wrong, no one is watching or testing. I suspect that the right to fail is a gift that most of us would enjoy.

Montessori schools utilize a similar approach in their classrooms. Their educational materials and challenges are organized in such a way that the room becomes child, rather than teacher centered. When each student is ready to proceed to the next level, the teacher demonstrates how to use equipment, grapple with new concepts, and complete exercises, but then the child is left alone to experiment or not. Once the task is mastered, the child often becomes inventive and employs the material in personal ways. New subjects are only introduced as the youngster develops skill and knowledge of previously presented challenges. All materials that have been mastered can be used and reused as the child desires. This method gives students freedom to roam throughout the classroom, choosing to advance according to their own wishes and developmental time line.

I remember my daughter zipping through math manipulatives as fast as they were presented. She perceived them as detective problems to be solved and looked forward to ever more demanding puzzles. My son took a different approach than barreling through the material. Once he mastered the fraction and bead boards in a way that demonstrated understanding, he went on to construct high rise buildings and bridges with the pieces. Both approaches were encouraged within this open ended learning environment.

When my children were young, I did not have a museum or classroom at hand, so my home became a place where I developed a similarly organized education playground. Influenced by Montessori’s approach, our basement space was thoughtfully and purposefully arranged. Shelves were filled with toys and games selected to develop math and language competency and analytic abilities by engaging in a variety of activities. There was never a need to sit still for long periods of time so they did not get bored and tired of hearing a talking head. Since the children were always free to choose what they wanted to do, without realizing it they improved their analytic and conceptual abilities and small and large motor skills. Their explorations helped them become more creative people as they imagined new ways of using their toys. As a mother I was pleased because they also learned to care for their materials by returning them to the shelf before proceeding to another activity.

Children’s and science museums are conceived as large scale exploration centers, making them lots of fun to visit. They mimic schools by having an educational bent, but differ in that their philosophy promotes a hands-on pedagogical approach to learning. Unfortunately entrance fees are expensive and trips to museums are not always practical, so it is up to the caregiver to provide exciting educational opportunities for the children in their charge. Families who want to supplement institutional visits need to focus on ways of stimulating their children’s sensory awareness, feeding their intellect and evoking emotional responses around social issues. But possibilities surround us everyday. As Sesame Street’s Grover Monster says; all you need to do is open the door to everything in the whole wide world museum.

I would love to hear your thoughts about educating children. Please comment below.

Art work is always for sale. Contact me at marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

Reference:

Grover and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum

by Norman Stiles, Daniel Wilcox, Joe Mathieu (Illustrator)

Home » Blog » Freedom to Fail

Table of Contents

Freedom to Fail!

One October day, while sitting in my museum office, I heard shouting and the sound of feet running towards my door. Needless to say, I was alarmed, and vaulted from my chair imagining that there had been an accident. Instead, I was greeted at the door by a mother and teacher who were extremely excited and wanted to share incredibly good news. A miraculous event had occurred during their visit; Jenny, a six year old autistic child, spoke for the first time.

The women had been exploring my small Lansing science center with their class of disabled students, but because they had several youngsters to oversee, their attention was turned elsewhere and the young girl had freedom to explore the exhibit hall on her own. She had stopped before an oscilloscope, picked up the microphone, and in order to see the wiggly voice patterns, started making sounds. Jenny became mesmerized with the moving lines and repeated several words over and over again. Without pressure to perform, the child had felt comfortable playing with the display in her own way. Eventually, the adults went to find her, and from a distance observed what was happening. They were so amazed and excited that they immediately ran to give me their wonderful news.

The teacher later shared that she had forgotten about the research that had been conducted with autistic children suggesting use of an oscilloscope to help patients vocalize. The day’s dramatic event reminded her of the study and she said that she planned to requisition a scope for her classroom in order to integrate it into a therapy approach with several other students.

The story does not end here, however. Mother, teacher and child returned to the museum several weeks later, and immediately dovetailed to the oscilloscope. The child was placed in front, handed the microphone, and told to talk into it, while the adults stood behind observing with high expectations of a repeat performance. Instead, they saw what some of you might expect . . . silence. And though they were disappointed in the child’s reaction, it fascinated me for it provided insight into human behavior that reinforced some of my assumptions about learning.

What did this incident teach me? First, it confirmed my belief that children need a rich variety of environments through which to roam. Secondly, it corroborated my opinion that youngsters need freedom to make choices away from the eyes of overly anxious adults.

What I like most about science centers and children’s museums is that they provide a safe environment for self-exploration. They are designed to enable visitors to learn in their own way on their own time scale. Parents do not need to hover over children and teachers are not charged with explaining what should be learned. A child exploring the interactive displays, experiments and forms his or her own conclusions. Very quickly the young visiter learns that it OK to be wrong, no one is watching or testing. I suspect that the right to fail is a gift that most of us would enjoy.

Montessori schools utilize a similar approach in their classrooms. Their educational materials and challenges are organized in such a way that the room becomes child, rather than teacher centered. When each student is ready to proceed to the next level, the teacher demonstrates how to use equipment, grapple with new concepts, and complete exercises, but then the child is left alone to experiment or not. Once the task is mastered, the child often becomes inventive and employs the material in personal ways. New subjects are only introduced as the youngster develops skill and knowledge of previously presented challenges. All materials that have been mastered can be used and reused as the child desires. This method gives students freedom to roam throughout the classroom, choosing to advance according to their own wishes and developmental time line.

I remember my daughter zipping through math manipulatives as fast as they were presented. She perceived them as detective problems to be solved and looked forward to ever more demanding puzzles. My son took a different approach than barreling through the material. Once he mastered the fraction and bead boards in a way that demonstrated understanding, he went on to construct high rise buildings and bridges with the pieces. Both approaches were encouraged within this open ended learning environment.

When my children were young, I did not have a museum or classroom at hand, so my home became a place where I developed a similarly organized education playground. Influenced by Montessori’s approach, our basement space was thoughtfully and purposefully arranged. Shelves were filled with toys and games selected to develop math and language competency and analytic abilities by engaging in a variety of activities. There was never a need to sit still for long periods of time so they did not get bored and tired of hearing a talking head. Since the children were always free to choose what they wanted to do, without realizing it they improved their analytic and conceptual abilities and small and large motor skills. Their explorations helped them become more creative people as they imagined new ways of using their toys. As a mother I was pleased because they also learned to care for their materials by returning them to the shelf before proceeding to another activity.

Children’s and science museums are conceived as large scale exploration centers, making them lots of fun to visit. They mimic schools by having an educational bent, but differ in that their philosophy promotes a hands-on pedagogical approach to learning. Unfortunately entrance fees are expensive and trips to museums are not always practical, so it is up to the caregiver to provide exciting educational opportunities for the children in their charge. Families who want to supplement institutional visits need to focus on ways of stimulating their children’s sensory awareness, feeding their intellect and evoking emotional responses around social issues. But possibilities surround us everyday. As Sesame Street’s Grover Monster says; all you need to do is open the door to everything in the whole wide world museum.

I would love to hear your thoughts about educating children. Please comment below.

Art work is always for sale. Contact me at marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

Reference:

Grover and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum

by Norman Stiles, Daniel Wilcox, Joe Mathieu (Illustrator)

Table of Contents