House Call

Medicine – What happened?

Medical care today is beyond my comprehension. As technology, sophisticated treatments, and pharmaceuticals improve, the quality of interactions between physician and patient appears to decline. Instead of getting to know patients and their families, doctors don’t take the time. Sick people marching through their primary care offices or visited online are treated as though they are robotic machines needing oiling. I don’t like it.

The last time I went for an annual check-up, the doctor sat in front of her computer, typing without looking up. She drilled me with questions, tested my memory, and wouldn’t discuss the list of issues that were on my mind. Believe me, when I say, my memory is good. I remember that visit in detail.

“You’ll have to come back for another appointment to talk about specialists,” she said at the end of the 15 minutes allotted to our session. I was shocked. Come back? Specialists? What happened to the general practitioner who listened to my heart, thumped my chest, and tried to answer the questions I brought with me to her office? I was told later that it was because of the way insurance companies were billed. Doctors make more money if they set up separate visits for each concern. I naively thought that primary care physicians were there to manage my health care, but learned quickly that if you are ill and need hospitalization, he or she won’t stop by the room to say hello or ask how I am getting along. There is no money in it.

My dismay came to a head recently when, after two nights in the hospital recovering from hip surgery, Ray, my partner, was discharged to recuperate from a hip operation at home. Two years earlier patients were typically kept under observation for five days or more after such a procedure. Watch out for blood clots, soreness around the wound, bathroom functions, don’t fall, and don’t get addicted to opioids were on the written instructions handed to him as we went out the door.

What bothered me most, however, was that no one called the next day to ask how he was doing or if I, untrained as a nurse, had a question. Neither a visiting nurse nor a physical therapist was sent to check on him. The first time we heard from the doctor’s office was two weeks later on a video conference call with an assistant. Ray was asked to remove his dressing under the very distant eye of a professional who had difficulty seeing the wound. A man we know who was similarly discharged after an operation died from a massive blood clot his first night at home. He might be alive today if he had remained under professional observation for a few days.

I realize circumstances are different today, and the medical profession has drastically changed the way it manages patient services since I was a child. I suppose I should not fret for fear of being labeled old-fashioned. However, as the daughter of a general practitioner watching her father called from bed three to four nights a week to see patients, I know the meaning of compassionate family care. Dad paid house visits and could assess what type of care they were receiving from their relatives. It wasn’t unusual for him to deliver a baby, remove a cyst, set bones, or stitch wounds since he managed all routine procedures.

His type of ministration was still practiced when my children were young. I never took a child with a high fever to a waiting room where other children might catch my child’s disease. And, I didn’t have to worry about who would care for my toddlers while seeking help for the one who was ill. Seeing a patient in a safe and timely manner was my doctor’s central concern and arrangements were made through the receptionist that worked for all.

As recently as ten years ago, my primary care doctor removed a non-malignant tumor from my neck. I was taken care of in his office and not sent off to a stranger to do something he was capable of doing himself. I trusted him, felt listened to, and well cared for. He participated in a group practice, so when he retired, I was given another physician to call my own. The service I now receive is not as thorough and the quality of interaction not as compassionate. If I mention a concern, though minor, without further inquiry I will be sent off to a specialist and get stuck with a consultancy co-pay four times higher than with my primary care physician. Answering 5-minute questions by phone can elicit a $100 to $200 charge to the insurance company.

Come on friends, neighbors! When you hear the health care system is broken, what you hear is correct. It is, and like a broken bone, needs fixing.

Please your thoughts below.

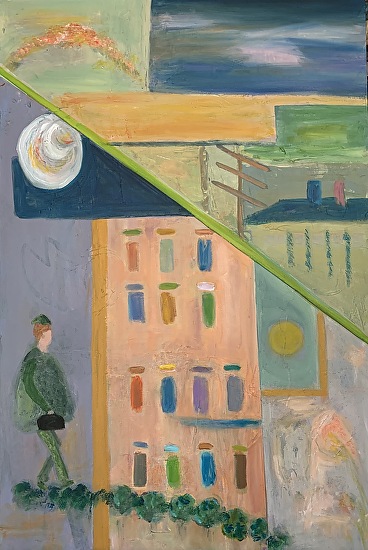

Art is always for sale. For information contact me at marilynne@eichingerfineart.com