Dear Friends: I would like to hear from you. Following is the introduction to Over the Peanut Fence and need to know if you would read a book like this. Your comments are invaluable to me at this time. Will you take a moment to respond?

Send comments to marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

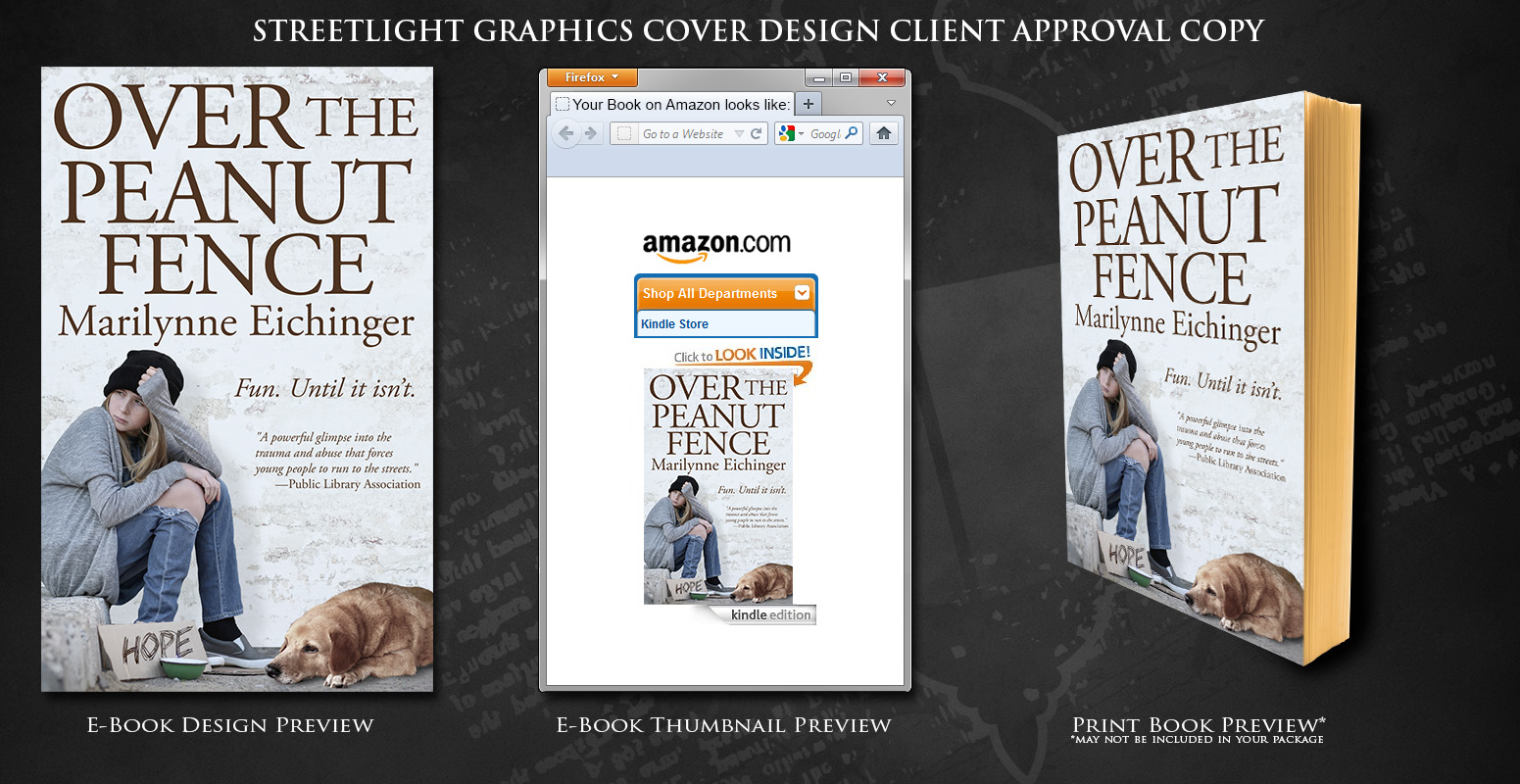

I am playing around with covers as well. Above is a potential design though it may not be my ultimate selection. It should help you understand the gist of the book. Do you find it appealing? Would you pick it up if you were browsing in a book store or on line?

Introduction

This is a tale of awakening, of learning to pay attention to shadows. It’s a quest to understand the lives of youths who struggle to survive—neglected, abandoned, homeless—living in hidden worlds far from the guarded, landscaped communities of social convention.

These youths are present at the periphery but rarely at the center of attention. Over a long and multi-faceted career, I frequently encountered homeless youths and, sometimes, their families, working to accommodate their needs so they could be included. More recently, I came face to face with the greater picture, the one in the shadows, the full immensity of the daily challenges faced by just one of these youths and I began to question, thus this tale.

As the former president of two museums and as owner of a catalog company, I interacted with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds and saw that the damaging effects of poverty are many and, at times, tragic. Even newly housed people face difficulties. Isolation behind closed apartment doors can be depressing for those used to socializing on the streets.

It was not until my partner Ray and I agreed to house Zach, a 19-year-old boy who survived four years living on the streets, that I became aware of youth homelessness. Though we knew Zach as a child, and threw peanuts over a fence to amuse him and five other siblings locked in their yard, we lost track until we saw him wandering aimlessly in Portland. He was ill, so we took him home for a week to bring him back to health and he wound up staying for five years. Over time, he became more literate, gained self-confidence and developed skills as a journeyman industrial painter.

Zach’s plight made me curious as to why youths are taking to the streets in record numbers. I wondered if stemming the growth of youth homelessness is possible. Teens run away for many reasons including poverty, drugs, mental illness, pregnancy, abuse, sexual orientation, and natural and man-made trauma. In each instance their developing brains are impacted. Care providers focus on interventions to help them become calm and improve their self-esteem.

Over the Peanut Fence is part memoir and part storybook about homeless youth, agency leaders, and volunteers. Tales are personal, like that of Kate Lore, who as a child, with her mother and sister, was locked out of a comfortable home and left to reside in poverty. Narratives explain how teens negotiate city streets in search of places to sleep, socialize, and eat. They reveal how much fun it is to be free from abuse and to meet others like themselves, and they tell of the depression that takes over when they see that their future prospects are poor.

As I shared information with friends, I soon realized how little most people know about youth homelessness. They, like I used to be, were quick to label street people as lazy, thieves, and drug abusers without understanding what brought them to their current circumstances. Fed by erroneous media reports, they believed that street youth are dangerous and commit violent crimes. Their perception is far from the truth. Rather than perpetrating crimes, homeless adolescents tend to be victims of criminal behavior and neglect which, in turn, toughens them up in order to survive.

Accordingly,“A recent study in Los Angeles puts a finer point on this information. Interviewing hundreds of street youth, homeless advocates found that 46% of boys and 32% of girls take part in “survival sex.” Of that group, 82% prostituted themselves for money, 48% for food or a place to stay, and a small group for drugs. A Hollywood study also found that half of the street youths sampled sold drugs. But interestingly, only one-fifth of that group–or, one in ten �of all street youths–sold drugs to support their own habit. The rest sold drugs as a means to earn money for food or shelter.”

Living on the streets is a relatively new phenomenon. Though there has always been mental illness, addiction, and domestic violence, widespread homelessness started in the 1970s, when the country stopped providing public housing for the mentally ill and the poor. Policies initiated by Nixon and Reagan continued under both Republican and Democratic presidents, worsening as the economy declined in 2007. Large numbers of unemployed adults began to self-medicate with alcohol and drugs. Often, depressed parents became abusive, neglected their children, causing them to take to the streets in record numbers.

I believe that government entities are unlikely to provide adequate funding, so the private sector will need to pick up the slack. Volunteers, schools, church groups, and youth agencies will have to join together and coordinate their efforts. Four years of research have provided me with reasons to hope. We can end youth homelessness because there are a great many people involved who care. Though cautiously optimistic that this societal problem can be solved, it will only happen if you and I step forward. This book is a call to action.

Home » Blog » Over the Peanut Fence

Table of Contents

Dear Friends: I would like to hear from you. Following is the introduction to Over the Peanut Fence and need to know if you would read a book like this. Your comments are invaluable to me at this time. Will you take a moment to respond?

Send comments to marilynne@eichingerfineart.com.

I am playing around with covers as well. Above is a potential design though it may not be my ultimate selection. It should help you understand the gist of the book. Do you find it appealing? Would you pick it up if you were browsing in a book store or on line?

Introduction

This is a tale of awakening, of learning to pay attention to shadows. It’s a quest to understand the lives of youths who struggle to survive—neglected, abandoned, homeless—living in hidden worlds far from the guarded, landscaped communities of social convention.

These youths are present at the periphery but rarely at the center of attention. Over a long and multi-faceted career, I frequently encountered homeless youths and, sometimes, their families, working to accommodate their needs so they could be included. More recently, I came face to face with the greater picture, the one in the shadows, the full immensity of the daily challenges faced by just one of these youths and I began to question, thus this tale.

As the former president of two museums and as owner of a catalog company, I interacted with people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds and saw that the damaging effects of poverty are many and, at times, tragic. Even newly housed people face difficulties. Isolation behind closed apartment doors can be depressing for those used to socializing on the streets.

It was not until my partner Ray and I agreed to house Zach, a 19-year-old boy who survived four years living on the streets, that I became aware of youth homelessness. Though we knew Zach as a child, and threw peanuts over a fence to amuse him and five other siblings locked in their yard, we lost track until we saw him wandering aimlessly in Portland. He was ill, so we took him home for a week to bring him back to health and he wound up staying for five years. Over time, he became more literate, gained self-confidence and developed skills as a journeyman industrial painter.

Zach’s plight made me curious as to why youths are taking to the streets in record numbers. I wondered if stemming the growth of youth homelessness is possible. Teens run away for many reasons including poverty, drugs, mental illness, pregnancy, abuse, sexual orientation, and natural and man-made trauma. In each instance their developing brains are impacted. Care providers focus on interventions to help them become calm and improve their self-esteem.

Over the Peanut Fence is part memoir and part storybook about homeless youth, agency leaders, and volunteers. Tales are personal, like that of Kate Lore, who as a child, with her mother and sister, was locked out of a comfortable home and left to reside in poverty. Narratives explain how teens negotiate city streets in search of places to sleep, socialize, and eat. They reveal how much fun it is to be free from abuse and to meet others like themselves, and they tell of the depression that takes over when they see that their future prospects are poor.

As I shared information with friends, I soon realized how little most people know about youth homelessness. They, like I used to be, were quick to label street people as lazy, thieves, and drug abusers without understanding what brought them to their current circumstances. Fed by erroneous media reports, they believed that street youth are dangerous and commit violent crimes. Their perception is far from the truth. Rather than perpetrating crimes, homeless adolescents tend to be victims of criminal behavior and neglect which, in turn, toughens them up in order to survive.

Accordingly,“A recent study in Los Angeles puts a finer point on this information. Interviewing hundreds of street youth, homeless advocates found that 46% of boys and 32% of girls take part in “survival sex.” Of that group, 82% prostituted themselves for money, 48% for food or a place to stay, and a small group for drugs. A Hollywood study also found that half of the street youths sampled sold drugs. But interestingly, only one-fifth of that group–or, one in ten of all street youths–sold drugs to support their own habit. The rest sold drugs as a means to earn money for food or shelter.”

Living on the streets is a relatively new phenomenon. Though there has always been mental illness, addiction, and domestic violence, widespread homelessness started in the 1970s, when the country stopped providing public housing for the mentally ill and the poor. Policies initiated by Nixon and Reagan continued under both Republican and Democratic presidents, worsening as the economy declined in 2007. Large numbers of unemployed adults began to self-medicate with alcohol and drugs. Often, depressed parents became abusive, neglected their children, causing them to take to the streets in record numbers.

I believe that government entities are unlikely to provide adequate funding, so the private sector will need to pick up the slack. Volunteers, schools, church groups, and youth agencies will have to join together and coordinate their efforts. Four years of research have provided me with reasons to hope. We can end youth homelessness because there are a great many people involved who care. Though cautiously optimistic that this societal problem can be solved, it will only happen if you and I step forward. This book is a call to action.

Table of Contents